It’s that time once again. Break out the Los Doggies Christmas Songbook. Be sure to add our OG Christmas songs to your yuletide playlist. And be sure to drink your Ovaltine.

PICO-8 Music

Born in the golden age of ’80s gaming, it was always my dream to become a real-life video-game composer. Now nearly one hundred years later, I’ve made that dream a reality with the help of PICO-8.

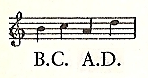

PICO-8 is a virtual console and game-making machine. The music editor looks like pic below. Instead of being read left-to-right like on manuscript paper, the music here is read vertically like Chinese or the Matrix. Does music move from side to side like a car, or does it cascade endlessly like rain? How does the trajectory of the musical engine dictate the character of the composition?

The PICO-8 is a very appetizing music-making machine. You can see two bars in a single snapshot with four instruments total, perfect to practice your four-part voice leading or minimalist acid-chip loops. The black background is preferred over white manuscript paper—musical notes hover over a black void of silence.

Just like real consoles, PICO-8 plays a boot-up melody when you open the app. The melody is a quick triplet of 3 tones—C, G, and F. Two intervals of fourths that move upwards. V to the I. A perfect cadence. Generally speaking, music wants to move up a fourth, like a chicken up a wire.

Compare this to the classic Game Boy boot-up sound. When you power on this fat grey brick with the spinach green screen, you’re treated to a flammy octave of C’s like a convenience store ding. Or in this case, a convenience store “blong.”

Music is infinite, so it’s nice to have some restrictions. The player will probably have to listen to your song a million times to complete the level. Sometimes the memory of the cartridge will only allow 16 bars per song. Game composition is all about writing the perfect short loop of music that won’t be too annoying.

Game designer Sourencho described what was needed:

Side note: I was thinking more about the music and I realized that for it to be “background”-y the changes that happen should feel like embellishments or variations on the base rather than “development” of the melody. That way it will feel like the music is changing but it’s not taking you somewhere higher or lower, or more important or climactic. Like if you stand in a forest the sounds are always changing because the wind hits different or a bird will start singing but the state of the forest isn’t changing dramatically as if a storm came through or a fire started. Static but with variation.

Beautifully stated. Better than I could do. I took it to mean an excessive amount of major seventh chords and constant modulations.

Anyway, here are a couple games I made music for.

Whippoorwill

I am the whippoorwill that cries in the night. No, actually—I’m just a guy. But sometimes I do cry in the night.

After sunset, you can hear whippoorwills sing their own name. Scientists call them “goatsuckers” in Latin. Guess how they got that name. There is not a poet born in America who hasn’t been wooed by these goatsuckers.

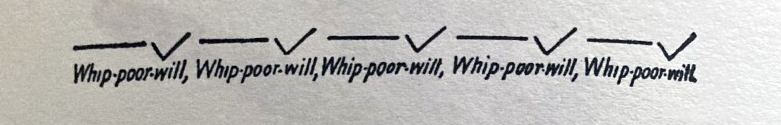

According to the great F. Schuyler Mathews:[1]

The song is weird; there is nothing like it in all of Nature’s music. It is a perfectly rhythmical, metallic whistle which could be written out intelligibly by a series of dashes, thus:

There are many possible musical transcriptions of the whippoorwill’s song. No two birds will sing exactly the same. Technically, it’s not even a song, and whippoorwills aren’t even songbirds. They just happen to perch on tree branches and make sounds to try to have sex exactly like songbirds do, but whatever.

This version fits nicely into A minor blues with a blue note. The phrase begins on an A root, followed by a quick triplet winding up from the sevenths, resolving on a quick minor third, and repeat. When slowed down, it sounds like there could be four notes instead of a triplet, so I took some artistic license above.

“Whip-poor-will” used to be spelt with hyphens a century ago. Nobody uses hyphens anymore, because they’re racist. “Whip poor Will,” and they bloody meant it! Lower class children were always getting beaten, especially when they grew too big to fit into the machines. There was an entire job known as “the whipping boy.” Modern ornithologists are wont to cover up this uncomfortable fact, but I’m on to those assholes.

I am the goatsucker that sucks goats in the night.

Notes:

[1] Mathews, F. Schuyler, (1921), Fieldbook of Wild Birds and Their Music.

Oatly Jingle

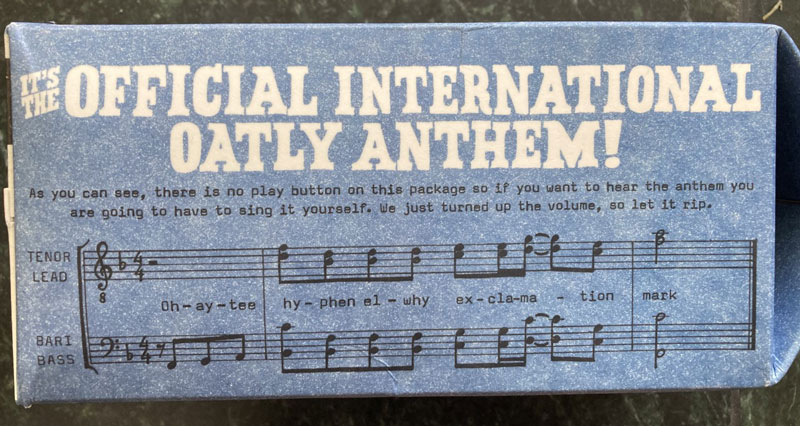

Companies have become so lazy, they don’t even produce jingles anymore. They just score them out on the side of their product and expect you to grab three of your friends from the barbershop to make it audible.

As you can see, there is no play button on this package so if you want to hear the anthem you are going to have to sing it yourself [on TikTok].

Oatly is a lazy company that makes horse milk for people. According to their jingle, there is a hyphen in their name, but as you can plainly see, there is no motherfucking hyphen anywhere. I guess they put it in there to make it work with the melody. There’s also no exclamation mark and it’s not an anthem, so the carton is very misleading. Who are the ad wizards responsible for this?

There’s a few good versions of the Oatly theme available on YouTube. This one’s probably the best, but you came here for the Los Doggies version, because nobody does it like the Doggies do.

You could also make it work by singing, “Ho-ly Oat-ly Ho-ly Oat-ly Oh!”

Between bail-outs, shrinkflation, silent jingles, and ESG scores, it’s almost like corporations don’t even care about making money anymore. They’re merely in it for the propaganda. Now, why would these globalist mega-corporations be pushing a radical new form of Marxism? I have no idea!

One day milk cartons will actually be digital and have play buttons on the side, but they’ll probably play ads. In my day, we displayed the victims of Satanic cults on the side of our milk cartons.

Joe Rogan drinks Oatly. So does Seabiscuit. If I’m at the store and I see a cheaper, larger, equine version of a product, I’ll usually opt for that.

Nailed It

There is a fine line between the spoken word and the musical tone. The more a phrase is repeated the more musical it becomes. This is illustrated in the speech-to-song illusion. Repeat a phrase over and over and listen as it magically transforms into a melody. This can be accomplished much quicker with sarcasm.

Sarcasm is inherently musical. It has a childish sing-song quality when used effectively. A phrase that leans sarcastic runs the risk of turning into a melody permanently.

A recent example can be heard in “Nailed it!” (see meme above). This carpenter’s phrase means to succeed in the manner of hitting a nail on the head. Casket builders also say it when they put the final nail in their coffins. But when the non-hammering public got a hold of the phrase, they started to use it in nailless situations, which began to sound increasingly sarcastic and less like speech, but rather some kind of gross proto-melody.

Behold and hearken, the Major Third that is “Nailed it!”

To my ears, this phrase usually fits a Major Third interval, although I can’t find any examples. Some people may say it in a Minor Third, but this is less sarcastic and might even imply success. The Major Third is probably the most sarcastic interval. I don’t know why. Maybe because it’s like an old-timey doorbell, where gags were expected at the door, whether a pail of water above or a bag of shit below.

Readers of this blog will recall the Major Third’s popularity can be traced back to Big Ben and its bell song. Perhaps the familiarity with this musical interval bred a kind of working-class resentment that expressed itself in a sarcastic phrase-melody. After all, the “Westminster Quarters” are played every quarter, four times an hour, twenty four times a day. That’s a lot of Major Thirds! English hammerers obviously got fed up with bells and nails.

So, what have we learned today? Repetitive speech can lead to sarcasm and music. Music and sarcasm are closely related and scientists are baffled. China doesn’t have these issues. They’re always speaking that Sprechgesang.

Losing Horn

I know well the feeling of watching an entire episode of The Price Is Right while eating an entire box of Triscuits. I’ve been a retired housewife most of my life.

How I dreamed of being on this show! I wouldn’t run down the aisles like the other Karens. I would stride confidently when my name was called to “Come on down!” I would take Barker’s massive leathery paw in my hand and give him the old politician’s elbow-hug. I alone would make it to the Showcase Showdown and spin the Big Wheel with the strength of ten contestants. How Barker’s Beauties would swoon!

In our last post, we covered the Duolingo Fail Sound and that got me thinking about the most infamous Fail Sound. When you think of failure, do you think of whammies? Or do you think of the “Losing Horn?”

Mmm, mmm, mmmmmmm. Like a bathroom full of tubas. This is the fail sound for fat losers. The sound of shabby hobos with outturned pockets. The sound of Bob Barker’s spoiled erection. No, wait, that’s just his pencil microphone. Before Curb Your Enthusiasm, this was our go-to tuba leitmotif for when shit got hairy.

Basically, what we have here is a perfect cadence (I V I). The final G on the bass sustains to create a C Major (2nd inversion). But instead of the high horns resolving nicely on the C and E, they glissando downward as of a Doppler Shift on a Häagen-Dazs truck.

In other words, the low horn asks a question, and the high horns provide a disappointing answer. They might even be mocking you.

After all, the models have cooled to your charms. The Big Wheel is stuck. The showcases have fallen. Bob looks ready to devour you if he doesn’t get his third rice pudding. Game over, man.

Duolingo: The Sound of Failure

In our last post, we covered the Duolingo “Sound of Success,” a happy Major Third inspired by door bells, store chimes, dial tones and car horns, which were in turn inspired by Big Ben’s bell song “Westminster Quarters.”

Now we turn our aural gaze to a more dissonant, evil sound—The Sound of Failure. If the Success Sound is designed to make you feel good by moving upwards in a happy interval, the Fail Sound is designed to open up the pit in your stomach and allow more room for sorrows and woes to swim inside your body and fill the emptiness that is you.

This interval from F# to C is known as a “Tritone,” a diminished Fifth or augmented Fourth. It takes the perfection of holy natural intervals and defiles them. The Tritone is the Devil himself appearing in music, or so they believed in the Dark Ages (back when you could openly beat a hunchback in the middle of the town square and nobody bat an eyelash.) Some middle-aged prudes in the Middle Ages (13-year-olds) even tried to ban the Tritone interval. It’s just that evil! And no Tritone is more evil than a Tritone in F-Sharp. It’s downright nasty.

If the Devil was Minister of Music in Heaven, got fired and fell down to Earth, it should follow that the Devil runs the terrestrial music biz as well. Take one look at the occult-laden sacred prostitutes of pop for proof.

Scientific experiments with babies show that babies prefer Major Chords to Diminished Chords. That’s because babies are winners, and devils are total fucking losers.

For pedagogical reinforcement, the Major Third Success Sound and the Tritone Fail Sound were finely selected by the Duotrope Sound Design team. Unfortunately, all of these sounds are really fucking annoying. Instead of “Westminster Quarters,” we have “Westminster Every 5 Seconds.”